You noticed that your child flaps their hands when they’re excited. Your teenager rocks back and forth while doing homework. Your husband hums the same tune over and over again. What is going on?

These behaviors might seem unusual at first, but they are examples of stimming, a natural and important part of how many people, especially autistic people, interact with the world.

Stimming often gets misunderstood. Some people see it as something that needs to be stopped or corrected. Others worry that it means something is wrong.

The reality is quite different. Stimming serves a real purpose, and learning about it can change how you perceive and support the autistic people in your life.

What is Stimming

Stimming is short for self-stimulatory behavior. That sounds clinical, but the concept is straightforward. It refers to repetitive movements, sounds, or actions that provide sensory feedback.

Think of it as the body’s way of seeking input or creating a specific sensation. When an autistic child flaps their hands, they are doing something that feels good or helps them manage what is happening around them.

When someone rocks in their chair, they might be calming themselves down or helping themselves focus. These are not random movements. They are purposeful, even if the person doing them cannot always explain why.

Here is something important to remember everyone stims from time to time. You too.

Ever tapped your foot while waiting? Twirled your hair during a phone call? Clicked a pen repeatedly? These are all forms of stimming.

The difference is that autistic people often stim more frequently, more intensely, and in ways that are more visible to others.

For autistic individuals, stimming directly connects to how their brains process sensory information. The world can feel too loud, too bright, or too overwhelming. Sometimes it feels too dull and under stimulating.

Stimming helps create balance. It is not weird. It’s adaptive.

The Many Forms of Stimming

Stimming does not look the same for everyone. It varies based on what sensory input a person needs or enjoys. Some people prefer movement. Others focus on sound or touch.

Here are the main categories:

Auditory and vocal stimming involves sound. This might mean humming, making clicking noises, repeating phrases, or listening to the same song snippet dozens of times. Some people repeat words they have heard, which is called echolalia.

This is not meaningless parroting. It often serves as a way to process language or express something when finding original words feels difficult.

Visual stimming centers on sight. Watching a fan spin, blinking in patterns, staring at flickering lights, or tracking moving objects all fall into this category. These activities provide visual input that can be soothing or satisfying.

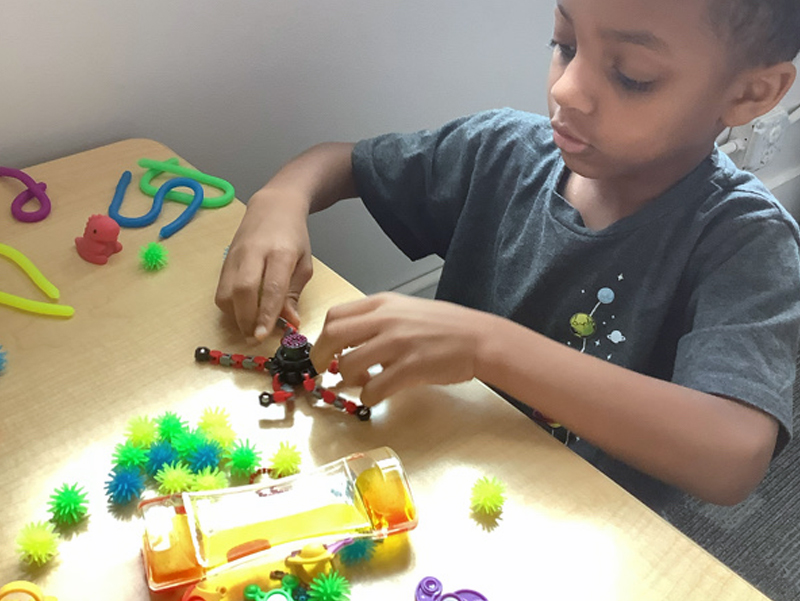

Tactile stimming involves touch. Running fingers over different textures, rubbing fabric, scratching surfaces, twisting hair, or touching smooth objects repeatedly all count. The physical sensation provides important feedback that helps with regulation.

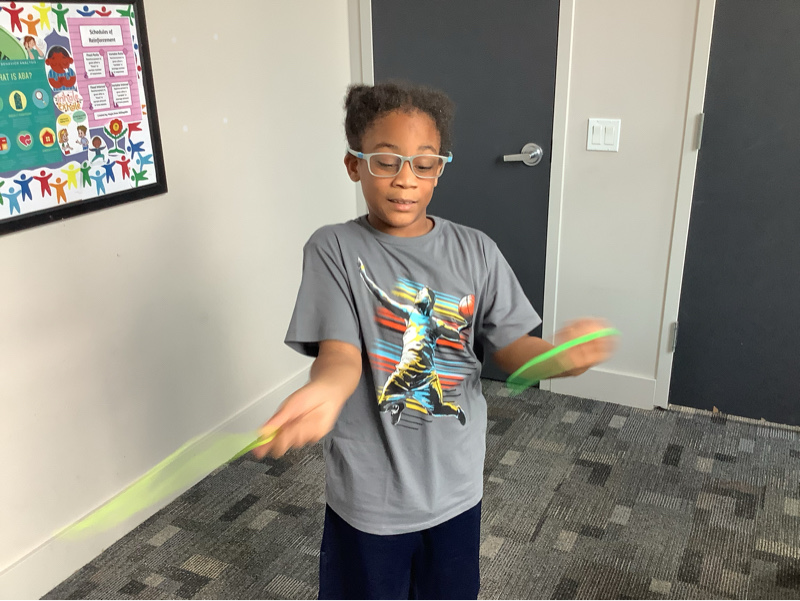

Vestibular and proprioceptive stimming relates to movement and body awareness. Rocking, spinning, jumping, pacing, swaying, or bouncing give information about where the body is in space. These movements can be calming or energizing, depending on what someone needs at that moment.

Oral and olfactory stimming uses taste and smell. Chewing objects, mouthing fabrics, smelling items repeatedly, or seeking specific tastes all provide sensory input through these channels.

What looks like “just” hand-flapping or rocking actually represents a sophisticated self-regulation system where each type of stimming serves a specific need.

Why Stimming Matters

Imagine feeling constantly on edge, unable to settle your nervous system. Or picture feeling disconnected from your body, like you are floating without an anchor. Now imagine having a tool that instantly helps. That is what stimming does for many autistic people.

Self-regulation stands out as the primary benefit. Life brings stress, anxiety, frustration, and overwhelming emotions. Stimming helps manage these feelings. When the world feels like it is too much, repetitive movement or sound can bring everything back to a manageable level.

When excitement bubbles up, stimming provides an outlet. It’s a release valve for the nervous system.

Sensory balance is another crucial function. Autistic brains often process sensory information differently. Sometimes too much comes in at once. The fluorescent lights buzz too loudly. The tags in shirts feel like sandpaper. Multiple conversations create unbearable noise.

Stimming can help filter or manage this overload. Other times, the problem is the opposite. Not enough is happening, and the brain craves input. Stimming creates that needed stimulation.

Communication happens through stimming too. When words do not come easily or when emotions are too big for language, stimming can express what is happening inside. Increased stimming might signal distress. Happy stims show joy.

For non-speaking autistic people or those who struggle with verbal communication, stims become a language of their own.

Pure joy deserves a mention. Not all stimming is about coping or regulation. Sometimes it is just fun. The feeling of flapping hands when something wonderful happens. The satisfaction of a perfect spin. The pleasure of a favorite sound. Stimming can be celebration.

Trying to stop these behaviors takes away essential tools. It’s like telling someone they cannot take deep breaths when anxious or cannot smile when happy. The behavior serves a purpose and removing it does not remove the need. It just removes the outlet.

When Support Is Required

Harmless stims deserve acceptance and respect. Hand-flapping, rocking, humming, spinning, finger-flicking, and similar behaviors do not cause problems. They might look different, but different does not mean wrong.

These stims should be allowed and even encouraged. Creating space for them shows respect for how someone’s brain works.

Risky stims need safer alternatives. Some stimming behaviors can cause injury. Head-banging, hitting oneself, scratching until bleeding, or biting hard enough to leave marks fall into this category.

These behaviors still serve a purpose. They are not manipulation or attention-seeking. They are attempts at regulation or communication.

The goal is not to stop the stimming but to redirect it. Occupational therapists can help identify what sensory needs the harmful stim meets and find safer ways to meet that need.

Chewy jewelry might replace biting. A crash pad could replace head-banging. Weighted items might provide the input someone seeks through hitting.

Disruptive stims sometimes need modification. If stimming prevents someone from participating in activities they want to do or need to do, some adjustment might help. This does not mean suppression.

It means finding ways to accommodate the need while supporting participation. Someone might need a scheduled stim break during class.

Perhaps they need a different learning environment that allows movement. Maybe noise-canceling headphones reduce the need for auditory stimming because they prevent overload in the first place.

The approach matters enormously. Punishment does not work and causes harm. Shaming makes things worse.

Instead, the question should always be: How can we support this person’s needs while keeping them safe and helping them access what they want in life?

Stimming Outside the Spectrum

Autism does not have a monopoly on stimming. People with ADHD often stim to help with focus and attention. Those with anxiety might stim to manage nervous energy. Even people without any diagnosis stim in various situations.

The difference lies in frequency, intensity, and connection to sensory processing. Autistic stimming tends to be more constant, more noticeable, and more directly tied to managing sensory input.

An ADHD person might fidget with a pen during a long meeting. An autistic person might need to rock continuously to manage the sensory experience of sitting in a bright room with humming lights.

This distinction matters because it prevents misunderstanding. What looks like lack of attention or defiance might actually be necessary regulation. An autistic student rocking in their chair is not being disruptive on purpose. They are managing sensory input so they can focus. Taking away the rocking does not improve attention. It makes focusing harder.

Other conditions can increase stimming too. OCD might involve repetitive behaviors, though motivation differs. Sensory processing disorder creates similar needs for sensory regulation. Anxiety disorders often come with self-soothing behaviors that look like stims.

The common thread is that stimming serves a function. It is not random or meaningless, regardless of whether someone is autistic. But recognizing the particular role it plays in autism helps create better support systems.

Creating Supportive Environments

At home, acceptance comes first. Let your child or family member stim. Do not discourage hand-flapping or humming unless it is causing harm.

Create a sensory-friendly space where they can engage in preferred stims freely. This might mean a room with dim lighting, soft textures, or space to move. Stock up on stim toys and tools that provide safe sensory input.

In schools, education is key. Teachers and staff need to understand that stimming is not misbehavior. A student who needs to pace or use a fidget is not being defiant. They are regulating so they can learn.

Flexible seating helps. Allowing movement breaks are effective. Not forcing eye contact during conversations shows respect. Creating quiet spaces where students can decompress prevents overload.

In public spaces, advocacy matters. When someone stares or comments on your child’s stimming, you can choose to educate.

A simple “They’re just happy” or “That helps them feel comfortable” can shift perception. You do not owe strangers explanations, but sometimes a brief comment helps.

More importantly, do not let others’ discomfort make you try to suppress harmless stims. Your child’s wellbeing matters more than a stranger’s confusion.

In workplaces, accommodation is possible. Adults who stim need supportive work environments too. This might mean allowing headphones, providing standing desks, or accepting that someone might pace during phone calls. Remote work helps many autistic adults because it allows stimming freely without judgment.

The goal is to build a world where autistic people do not have to mask or hide their natural behaviors. Masking takes enormous energy and causes actual harm over time. When someone has to constantly suppress stims, they have less energy for everything else and burnout becomes more likely. Mental health suffers.

Changing the Narrative

For too long, autism was framed entirely around deficits. What can’t autistic people do? What is wrong with them? How can we make them more “normal”?

This perspective misses something fundamental. Autism is not a collection of broken parts. It is a unique way of experiencing and processing the world. Stimming perfectly illustrates this.

From a deficit perspective, it is a problem behavior to eliminate. From a neurodiversity perspective, it is a natural and helpful adaptation.

When we tell autistic people to stop stimming, we say “Your natural way of being is wrong. Hide it to make others comfortable.”

That message causes real damage. It teaches autistic children that something is fundamentally wrong with them. It forces adults to spend exhausting energy masking. It creates shame around behaviors that should be neutral or even celebrated.

Shifting this narrative means several things. It means instructing non-autistic people about stimming, so it seems less strange. It means creating environments where stimming is accepted.

It means stopping therapies focused solely on making autistic people appear less autistic. It means asking “Is this behavior harmful?” rather than “Does this behavior look weird?”

Some parents worry that allowing stimming will make their child stand out more or face bullying. This concern is real. But the solution is not to force children to suppress their stims. It’s to create more accepting communities and teach peers about differences. It’s to give autistic children confidence in who they are so they can self-advocate. It’s to address bullying rather than asking autistic children to hide.

The Big Picture

Stimming connects to larger questions about acceptance and inclusion. When we make space for stimming, we are making space for diverse ways of being. We are acknowledging that there is no single “right” way to move through the world.

This matters for autistic people, obviously. But it also matters to everyone else. When we create more flexible environments that accommodate different sensory needs and diverse ways of regulating, everyone benefits.

A person with anxiety who needs to fidget. The ADHD student who needs to doodle to focus. The stressed employee who needs to pace while thinking. More inclusive environments are a win for everyone.

We are slowly moving in this direction. Fidget tools have become mainstream. Standing desks are common. Sensory rooms appear in more schools. These changes help, though there is still far to go.

The real shift needs to happen in attitudes. Stimming needs to become normalized, not just tolerated. We need to reach a point were seeing someone rock or flap their hands does not trigger stares or comments.

You can support the autistic people in your life by accepting their stims, creating space for them, and advocating for environments where stimming is welcomed. You can educate others. You can push back against therapies focused on suppression. You can listen when autistic people tell you what they need.

Most importantly, you can shift your perspective. Stop seeing stimming as something to fix. Start seeing it as something to understand and respect. That single change can make an enormous difference in an autistic person’s life.

Frequently Asked Questions

Should I try to stop my child from stimming?

No. Harmless stims like hand-flapping, rocking, or humming serve important purposes. Trying to stop them can increase anxiety and take away a valuable regulation tool.

Only redirect stims that cause injury or truly prevent your child from participating in activities they want to do. Even then, the goal is finding safer or more functional alternatives, not elimination.

What if my child’s stimming bothers other people?

This is difficult because the answer depends on the situation. In public, remember that your child’s needs come first. Harmless stims should be allowed even if others find them unusual.

You do not need to make your child suppress natural behaviors to ease strangers’ discomfort. However, you can instruct your child about different contexts. Some places might require quieter stims or shorter stim breaks. This is about flexibility and choice, not shame.

How is stimming different from tics?

Tics are involuntary movements or sounds. People with tic disorders cannot control when tics happen, and trying to suppress them creates significant discomfort. Stimming is voluntary and serves a purpose.

Autistic people can usually stop stimming if needed, though doing so takes effort and energy. The key difference is control and function. That said, some autistic people also have tic disorders, which can make this distinction blurry.

Are fidget toys the same as stimming?

Fidget toys can support stimming needs, but they are not exactly the same thing. A fidget spinner or stress ball provides sensory input, which can meet the same needs that stimming meets.

Many autistic people find fidget tools helpful, especially in settings where their preferred stims are not possible. However, these tools work best when they are offered as options, not forced as replacements for natural stims.

Can adults with autism stim too?

Absolutely. Stimming is not something people grow out of. Many autistic adults stim regularly, though some have learned to mask or hide their stims in certain situations. This masking often comes at a cost, leading to exhaustion and burnout. Creating spaces where autistic adults can stim freely is just as important as allowing children to stim.

What if stimming is increasing suddenly?

Increased stimming usually means something has changed. Your child might be more stressed, anxious, or overwhelmed. They might be experiencing more sensory overload. Sometimes increased stimming shows up during growth spurts or developmental changes.

Look for patterns. Did school get harder? Did routine change? Is there more noise or visual stimulation than usual? Address the underlying cause rather than focusing on the stimming itself.

How do I explain stimming to family members who do not understand?

Start with relatable comparisons. Most people tap their feet, twirl their hair, or pace when thinking. Explain that stimming is similar but more pronounced because of differences in sensory processing.

Share that it is helpful, not harmful. If family members are receptive, point them toward resources or articles about stimming. Sometimes hearing information from multiple sources helps it sink in.

Should stimming be included in therapy goals?

This depends entirely on the situation. Therapy should never aim to eliminate harmless stims. However, occupational therapy might appropriately address harmful stims by finding safer alternatives.

Speech therapy might work on communication so someone can express needs without relying solely on stims. The key is that therapy should support the autistic person’s wellbeing and goals, not make them appear more “normal.”

What is the difference between happy stimming and distressed stimming?

Context and body language usually make this clear. Happy stims often happen during enjoyable activities and come with smiles, laughter, or exciting vocalizations. Distressed stims might be more intense, faster, or paired with signs of discomfort-like tears or attempts to escape a situation.

Over time, you will learn to read your child’s individual patterns. What does their stimming look like when they are excited versus when they are overwhelmed?

Can stimming change over time?

Yes. Someone might prefer hand-flapping as a child but switch to subtler stims as an adult. New stims might develop while old ones fade. Changes in sensory needs, environments, or circumstances can all affect stimming patterns.

This is normal and does not indicate a problem. As long as the person has effective ways to regulate, the specific form does not matter much.